To Skin A Catcaller

To Skin a Catcaller (2015)

8 Hour Durational Performance

ATA Gallery, San Francisco

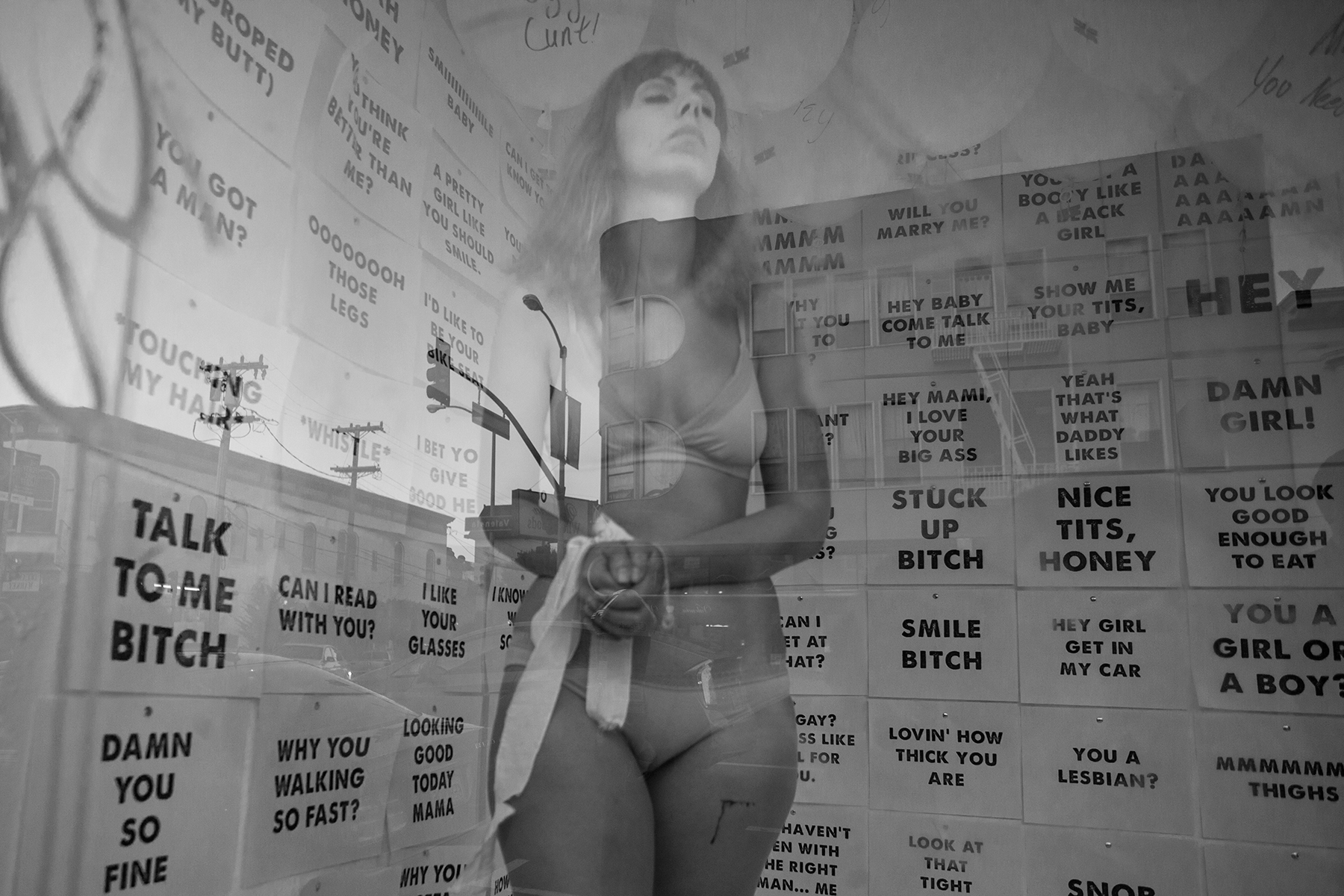

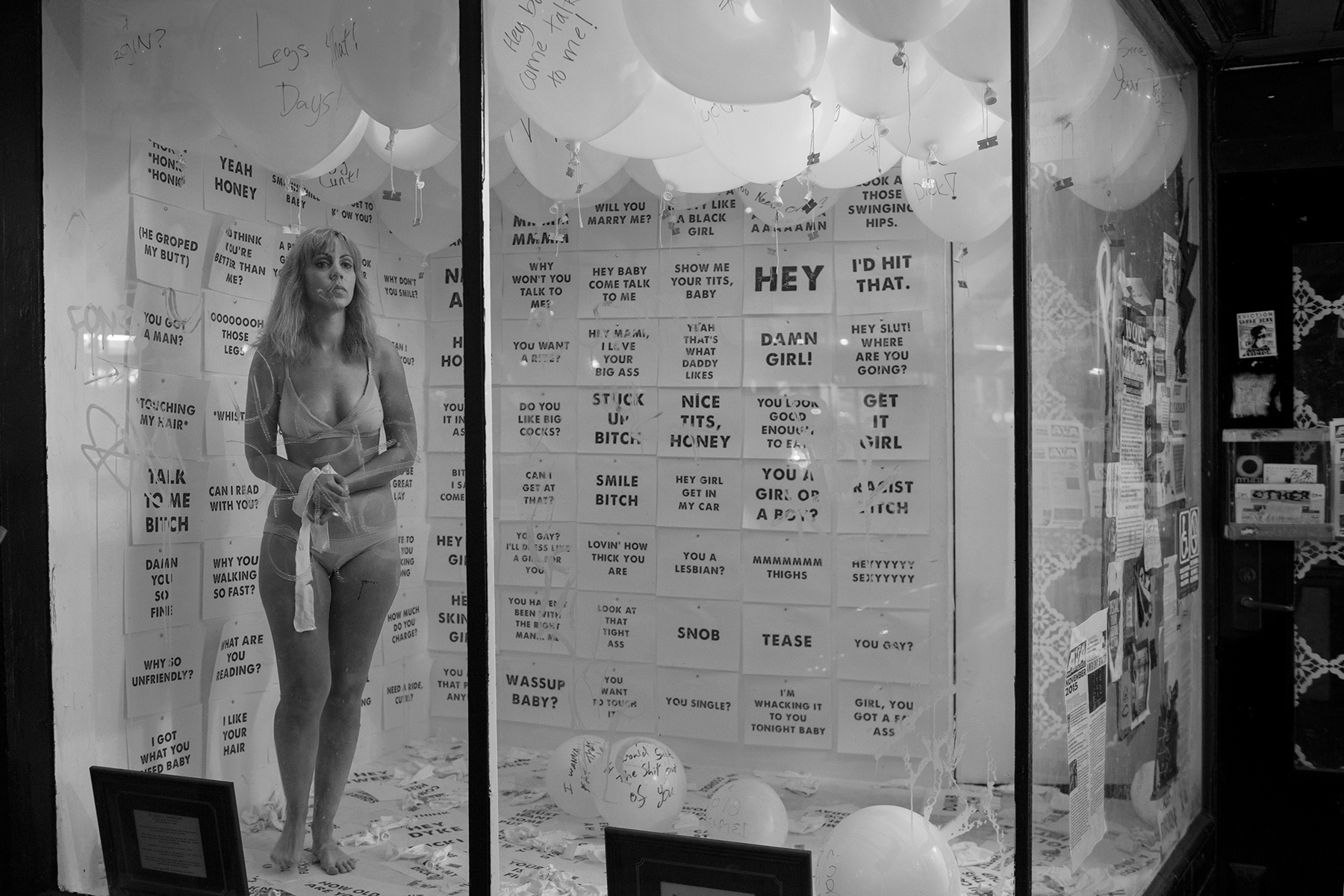

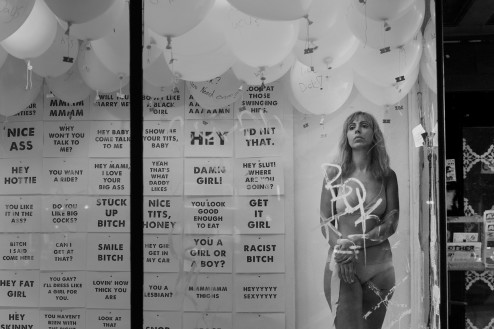

To Skin a Catcaller was an 8 hour endurance performance about street harassment and catcalling that took place at ATA Gallery in San Francisco in November 2015. In this performance, the artist navigates a 7′ x 7′ street-facing gallery window in a nude two piece while listening to real life catcalls for eight hours straight. As they navigate the space, catcalls scrawled onto oversized balloons dangling razor blades are inserted into the room forcing them to have to crouch, contort and otherwise maneuver to continue to navigate the space while avoiding violence. The story went viral and appeared in several news sources including the Huffington Post, .Mic, ATTN, Refinery29, Bustle, and more bringing international attention to the reality of how street harassment encroaches on people’s right to safety in public spaces. What resulted was a global conversation about how street harassment not only affects an individual’s psycho-physiological state including physical / mental health, but how this supposed “individual experience” when magnified to be viewed as a manifestation of violence against persons of targeted gender(s), races, and abilities negatively impacts society as a whole. The following is a first-hand account of the experience.

It’s nearly noon and I’m running late for my performance. As I hustle my way down Mission St. I hear a man making psst psst psst sounds, like he’s calling a cat. As I pass, I hear him say in a low voice, “oooooh girl I like that ass.” I turn a corner and another man leaning against a wall stands to place himself in front of me. He’s got a good hundred pounds on me and is a foot taller. My muscles tense. As I move to step around him, he grabs me by the arm and tells me that I’m beautiful and should smile more.

I’m almost to the gallery now when a man crosses the street and walks straight towards me. He stretches his arms out as if to grab me. I dodge him. “I had to cross the street to tell you your hair is awesome,” he says coming towards me. Now is not the time to explain to him that as nice as his intentions may be, the attention is not welcomed, that a stranger crossing the street to tell me anything short of “there is a big rock about to fall on you” is not something that stranger “has to do,” that because I get catcalled nearly ten times a day ranging from “hello” to “I want to lick your pussy” that I’d rather just be able to get from point A to point B without being showered in “compliments,” and that as a sexual assault survivor I have experienced the worst of “unwanted attention” and street harassment serves as an everyday reminder that rape culture persists. Instead of explaining all this, I invite him to my performance. “It’s about street harassment and catcalling.” He’s stunned as I brush past him but a block away I can hear him laughing. Before I turn the corner I look back and see him standing now in the middle of the street, shouting to whoever is within earshot, “What a bitch! What a crazy fucking bitch!”

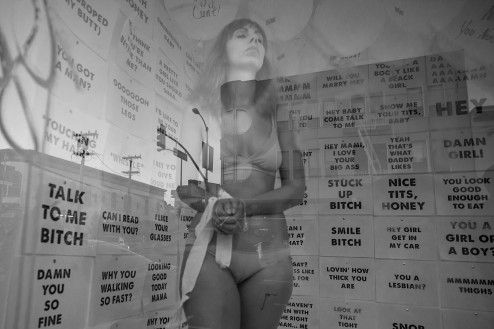

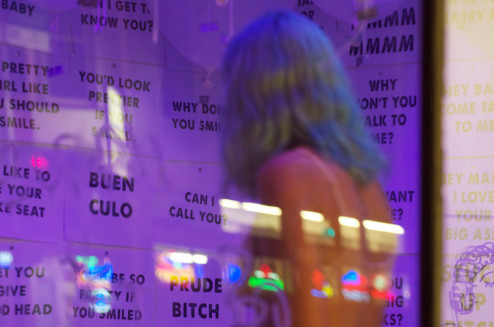

I reach the gallery and climb into the familiar tiny 6′ x 7′ space of the window. I say familiar because a year ago I spent 12 hours here inside a small glass case sitting with my legs pressed to my body, unable to move. This time, the gallery walls and floor are plastered in white pages with block letters displaying a slew of catcalls ranging from “You look beautiful” to “I’m going to follow you home and fuck you in your sleep.” It may sound extreme but violence and threats are by no means uncommon in the repertoire of catcalls and all 200 of the catcalls that grace the gallery walls today are real.

I know they’re real because I sourced them myself through a catcalling survey I put out on social media. I decided that if I received no or few responses, I would agree that catcalling “isn’t a serious issue” and not pursue this performance. In one week, I received over 100 responses. This was not shocking to me. In my work serving as co-organizer with Genevieve D. Berrick for Hollaback LA! I’m aware that street harassment affects many more people than the silence in the media about it would have one believe.

The responses I received were not just numerous; they were thorough and passionate. Not one female-identified participant said she had NEVER experienced street harassment. Not one said the harassment they’d experienced was complimentary, “harmless” or non-threatening. Participants cited everything from verbal assault, to groping, sexual assault, stalking, racism, homophobia, transphobia, sexism, and hate speech. Many admitted to having made changes in their clothing, their choice of whether to walk or take public transit, and changes in their willingness to interact with strangers, particularly men. Some admitted to suffering from agoraphobia or refusing to leave the house without someone to accompany them. All admitted that pervasive street harassment had changed not only their behavior but also aspects of their personality, their feelings of safety, their ability and freedom to be themselves in public space.

“Bitch I said come here! / I want to cum all over that. / Where’s your boyfriend? / Do I scare you? / Smile!”

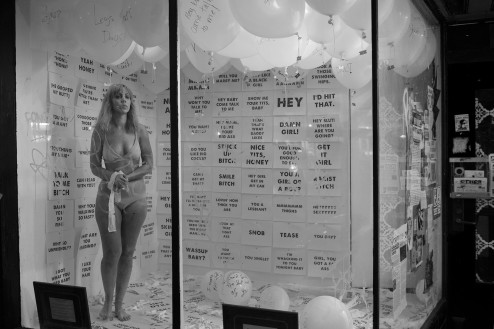

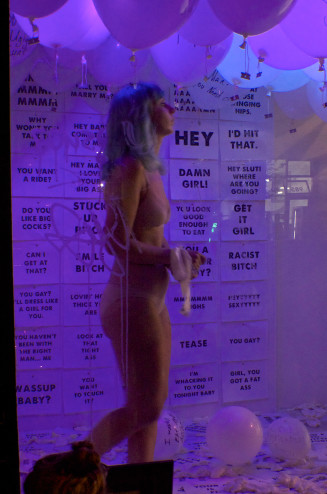

Today I will get to know these and the 195 other catcalls I’ve sourced from the surveys well. For eight hours, I will be confined to walking around the edges of the tiny window gallery listening to them echo over and over again through a loud speaker that blares out on to the street. I will hear each one of the 200 catcalls 48 times throughout the performance. Every hour, I will experience new constraints to symbolize threats of violence. My clothes will be removed. My hands will be bound. At one point I will be blind folded. Every hour, oversized balloons representative of bodies with catcalls scrawled across them and razor blades dangling just above my head will be added to the room, limiting the space in which I am free to move and increasing the hostility of the environment around me. Eventually, razor blades will be added to the floor. Like people do everyday on the streets, I will have to make decisions about what spaces in the gallery are still safe for me to move in without coming too close to violence to escape it.

As the balloons begin to fill the gallery, marking the beginning of the performance, I prepare myself to the very real sensations I know can come from street harassment: loss of safety, fear, confinement, being trapped, exhaustion, lack of esteem, lack of confidence, body dysmorphia and other body image disorders, agoraphobia, depression, anger, lack of agency, feeling gaslighted, feeling ugly, wanting to hurt someone, wanting to hide, wanting to disappear.

During the course of the eight hours, I experience all of these emotions as do many who stop to watch me with a look of familiarity in their eyes that says the piece resonates with their experience. A woman holds her hand against the gallery window and leaves it there for a long time, smiling at me with great kindness. Another grabs people from the street, telling them to come and watch. In an excited voice, as if declaring “finally somebody gives a damn!” she explains to them that the performance is about catcalling. As I continue to pace, hour after hour, I see mothers and fathers having difficult but tender conversations with their children about the treatment of women in public space. On the sidewalk, I’ve left a book for passersby to share their catcalling experiences. I receive pages and pages of responses from locals and non-locals alike. When I have a chance to read them later on, I will learn that many share sentiments with the participants who took my survey. Many say they’ve experienced ongoing street harassment. Some have been groped or physically assaulted. Some don’t leave the house if they can help it. Some have been experiencing street harassment since they were as young as nine years old but have never spoken up about it until now.

Not everyone responds with empathy. Throughout the day, there are men who enticed by my lack of clothing stand and stare at me. When they realize through the audio loop and visual cues that they are watching a performance about catcalling, some take off. Others stay, like the man who stands licking his lips at me for a full ten minutes until a male friend comes out of the gallery. It’s a common case with catcallers: they high tail it if they sense you are another man’s “property.” Another group of men stand, point, laugh and make comments about my body, especially my breasts and ass, as if weighing their value. There are groups of men who argue on the sidewalk about whether or not I as a woman have the right to object to catcalling. “Those are just compliments,” one says. “Women should be grateful they get that kind of attention,” says another.

This attitude, this obliviousness, is echoed in some of the entries in the book I left on the sidewalk. One person writes, “While I was watching your performance a man came and stood next to me. ‘That’s a nice picture,’ he said. ‘There should be a man in there with her.’ And then he laughed. I think he missed the point entirely.”

I think about these statements as I navigate the gallery, the repetitive motion making me light-headed and dizzy to the point of nausea. I think about how women are often told they should not be upset about catcalls. “They’re just compliments,” is a common refrain. Looking at the mass of black text in front of me, I remind myself that when placed in the context of the tremendous onslaught of unwanted verbal acknowledgements women receive every day that even a “hey why don’t you smile” can be insanely irritating, can even serve as a reminder of trauma for the one in six of us who have experienced sexual assault. And while society offers many tips for women on how to “handle” catcalling such as wearing headphones or sunglasses, dressing conservatively, or keeping your head down, the reality is that no one should have to do anything. Street harassment should not happen and the burden of maintaining one’s safety should not fall on the victim because they’ve done nothing wrong. These are the thoughts which keep me in motion, even as the difficulty in doing so increases hour after hour, the space I have to move in narrowing, the blades above coming closer to my skin.

Sometimes threats of violence lead to violence. I’m midway through, and there are so many balloons in the space I can barely move. I am practically crawling on the floor in order to continue to navigate the space. My spine and legs ache. My arms are bound. The blades graze my head, my shoulders, my arms. Suddenly the door opens and another balloon is added to the space. It drifts up. There’s a pop, and a moment later a bang bang bang. The stray balloon has hit another and set off a chain reaction. Blades fly everywhere. It is all over in matter of minutes but that minute is terrifying. It is not until I see someone taking a photo an hour later that I realize one of the blades has sliced a gash in my thigh. Weeks later, I’ll bear a scar.

I’m nearing the last quarter when, exhausted from navigating the space, from being stared at, from the ongoing auditory berating that blares over the speaker, I don’t have the energy to navigate the space clearly. One misstep and I feel a shooting pain in my foot. I continue walking but notice as I complete my first loop that there is blood on the floor. The blade has gone into my foot and the cut is deep. For the next two hours, I will bleed onto the pages with every step until the performance has reached its terminus.

I’m almost to the end of the 8 hours. I look into the faces of those watching me and one by one, I display each catcall to the small crowd watching from the street. I take a moment to acknowledge familiarity in the eyes of those watching before pressing the razor to the soft latex edge of the balloon. With a bang it deflates. I do this for the each of the remaining balloons and crumple each catcall into a ball, throwing them against the door. With every burst balloon and crumpled page, I feel a little more free, having rid myself of the threats around me that have tortured me for the last eight hours. At last, all that remains in the gallery is myself and a pile of crumpled, deflated insults. Nina Simone once said that to be free is to live without fear. And for a moment, for this one moment, that is how I feel. I feel free. To live in a world without fear, to be truly free, more than anything I wish we could all live that way.

Video by Lieven Leroy / Subversive Photography:

This performance occurred in the ATA Gallery Window at ATA Gallery in San Francisco. It was a part of the series “Almost Public / Semi-Exposed II” curated by Tessa Siddle and Ariel Zaccheo.

Thank you to the following individuals with whom this performance could not have happened: Tessa Siddle, Ariel Zaccheo, Bella Donna, Tara Sullivan, Ben Joeng, Crutcher Dunnavant, Chris Warfied, Katy Pelton + Todd Huffman, David Singer, Erik O., and Charles. Thank you to photographers Lieven Leroy and Tim Guydish.

Photos copyright Lieven Leroy Subversive Photography or Tim Guydish