109 Seconds: Invisible Weight

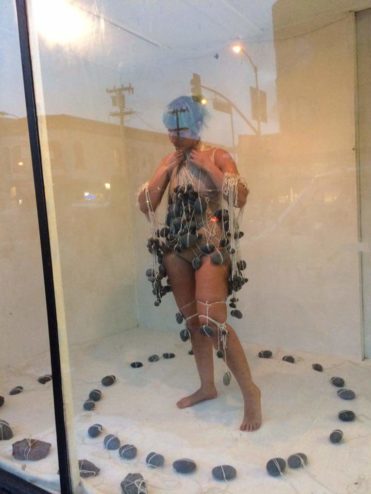

109 Seconds: Invisible Weight (2016)

6 Hour Durational Performance

ATA Gallery, San Francisco

This performance references the fact that every 109 seconds, someone in the United States will be sexually assaulted. For six hours, I occupied a street-facing gallery window on Valencia Street in San Francisco. Every 109 seconds, a stone varying in weight would be hung from my body and at the same time a survivor’s account of a sexual assault would be echoed over the loud speaker. Each account was followed by words of strength and encouragement for other survivors. After 6 hours, the total weight hung from my body matched my body weight and I collapsed. The performance took place at ATA Gallery in San Francisco in November 2016. The following is a written documentation.

In the time it will take you to read this 27 people in the United States will have been sexually assaulted. Maybe you’d like to stop reading. Maybe you’re thinking, “I don’t want to read this right now.” That’s okay. But I hope you’ll continue. Not because you’d like to, but because sometimes we need to hear stories that aren’t likeable. We need to hear them because they’re true.

I was standing in the window of a gallery on Valencia street in San Francisco wearing a flesh-toned bodysuit. Positioned around me were several concentric circles of twine-wrapped stones. The stones were of various weights and sizes: some smooth dark pebbles weighing only a pound, some jagged rocks the size and weight of my own head. The combined weight of the stones matched that of my own body weight: 120 lbs.

Photos by Julia O. Test // http://www.juliaotest.com/

My eyes traced the ring of stones then drifted up to the busy street- buses and cars and bicycles all jammed together, tourists swinging shopping bags, transplants with startup shirts talking on their iPhones. It was cold out but the hair on my arms stood on end for other reasons; I hadn’t rehearsed or trained. What if I couldn’t do it? What if I failed?

I didn’t have much time to think about it before the clock struck noon. I spread my arms up and out, palms down. I listened as the door behind me opened and shut. I felt a tug on my forearm as the first stone was hung from my body. At the same time, a voice echoed over the loudspeaker aimed at the sidewalk, “The morning after I was raped the first time, I made my rapist breakfast…”

I listened as a friend recounted her assault, stressing how survivor narratives often don’t fit the script of rape as penned by society. That narrative looks something like: A stranger in a dark alley with a gun. A broken (usually white) woman running to the police in tears. These are the kinds of reports that might—if you’re lucky—lead to some form of conviction. But often stories of sexual assault are more complicated, just as all true stories are, and these stories rarely end in justice.

“If your story is complicated too,” the recording concluded, “you’re definitely not alone.”

In the silence that followed, I considered what I was doing. Was I sending a good message? Sure, I had placed trigger warnings along the sidewalk, but was it right to share these stories publicly?

109 seconds passed and I heard the door open once more. I closed my eyes as one of the heavier stones was hung around my neck, choking me. It nearly threw me off balance but I steadied myself and managed to swing the stone with my neck to one side, freeing my throat. Shortly after, the next story began, “My first boyfriend was eager to have sex. I didn’t want to.”

This story could have been my own in another’s voice. I was 14 and thought rape wasn’t something that could happen if you were in a relationship with your rapist. Even though I’d said “no,” it wouldn’t even cross my mind that it had been rape until I was sexually assaulted again a decade later. At the time I thought, “oh so this is what sex is. You might say no and someone might do it anyway and you should lay back and pretend to like it.” I couldn’t have known better. It was my first time.

The recording finished and another 109 seconds passed. And then another. Each time, a new stone of varying weight was hung from my arms or neck. The first four hours were the worst, as I struggled and failed to consistently keep my balance, keeping my arms raised as much as possible but feeling the weight increasingly pulling me down. By the fifth hour, I had given up on struggling, had almost become accustomed to the squeezing of the blood flow by the ropes tugging at my limbs, trying to pull me to the floor. What had started as wings of pebbles draped from my arms was now a heap of granite anchored to my 5’2” frame. That was fine. It was the stories that were bearing down on me.

No two accounts were the same and the vast majority didn’t fit the stranger = danger narrative. There were stories of wives assaulted by their husbands. Stories of women cornered in stairwells or frat dorms, at their babysitter’s house, camp, in a dressing room, at school. Stories of children assaulted by their uncles, grandparents, parents- who were told to keep quiet because “it’d break up the family.” Stories of survivors who’d been told by the police they’d been “asking for it” because they were at a club drinking, dancing with their rapist. “How could it be rape? You liked him, right?” There were stories of queers and people of color whose reports were not taken seriously because of their gender or the color of their skin. “But you’re both gay right?” With each story I was reminded of what we all share- the weight of having to carry those stories inside of us at all times and the stress and vulnerability that comes when we attempt to air them. I was reminded of the work that comes with having to justify your trauma as real. The uncertainty as to what good it’ll even do in a society so quick to interrogate survivors instead of confronting abusers. Those stories, all 165 of them, wore heavy on me. And I still had an hour to go.

Barely holding myself upward, I approached the final stretch. With each new stone attached to different points of my body (which now included my legs and pelvis because I had no space open along my arms and neck) I felt certain I would drop. Intermittently crowds gathered to watch- some lingering below the loudspeaker listening knowingly, some putting their hands up to the glass, some bursting into laughter which they quickly reeled in after reading the description hung in the window detailing the nature of the performance. And even then there were some who continued to laugh, to point, to harass or stare at me, some even lecherously, even after they realized this was a statement about sexual violence. I stared straight ahead during these last encounters. I didn’t flinch. I couldn’t. I refused to give them the pleasure.

A group of teenagers came by several times throughout the performance to check up on me. Through the glass I could hear them scream, “You can make it!” I could see it in their faces that they already knew too well what sexual assault was. One girl was particularly quiet and could hardly look at me. My heart went out to her whenever they came by to cheer me on.

It was people like them and the large crowd who gathered towards the very end that got me through that final stretch. As the last stone, a ten pound boulder with sharp edges, was hung from my neck, scraping against my chest, I barely made out the sound of my own voice, my own story, ringing out over the dark, rain drenched sidewalk. “The officer assigned to my case told me there were 180 cases just like mine on her desk before closing it. My rapist never suffered more than a phone call.” As the recording ended, I fell to the floor.

The stones were cut from my body and after some time I stood up again. My body pulsed with pain and exhilaration. I had done it. Somehow, I had reached the end.

I thanked the crowd that had gathered and those who helped before loading my materials into the back of my truck. The last of these was a handmade book I had left on the sidewalk for survivors to share their thoughts. I opened it to a page at random and read the words, “My girlfriend was assaulted last month and I’ve been trying to support her. She blames herself for what happened even though I tell her over and over again it’s not her fault. She says I should leave her because of what happened but I won’t do that. It’s devastating she has to feel this way. What you’re doing is needed so people like her know they aren’t alone and they aren’t to blame. Thank you.”

I’ve been hesitating to share this— maybe it’s not the right time. Maybe there’ll be a time when current political and cultural affairs aren’t overwhelming survivors with sadness, anger, and disappointment—but I know that time will never come. I was going to let the experience fade into memory but then I thought if I needed a reminder that neither the past nor the present dictate the possibilities of the future, maybe others do too.

Dear Survivors: The system is broken. You are not. You’re rebuilt. And the times when we feel the greatest weight pressing down on us are the times when we need most to push back. We’ve grown stronger for having lived through our experiences. We carry that invisible weight with us every day. But we carry it together. Survivors are the strongest people in the world. And together we will show our strength.

Mirabelle Jones is a writer, performance artist, and visual artist from Oakland, CA. In 2015, her performance To Skin a Catcaller brought international attention to the subject of street harassment. She is the founder of the grassroots collective Art Against Assault which seeks to raise funds for survivor resources while nurturing the production of survivor-initiated creative works.

Thank you to: Anouk Wipprecht, Bella Donna, Crutcher Dunnavant, Robin Gee, Alexander Cotton, Zarinah Agnew, Julia O. Test, Lieven Leroy, Tim Gyudish, ATA Gallery, Tessa Siddle, Ariel Zaccheo, and to all of the survivors who contributed their narratives to this project as well as to survivors everywhere.